With advances in generative AI and computational processing we are in midst of a paradigm shift is forcing researchers, designers, communicators and storytellers to re-evaluate the value of photography in our work.

This article outlines the Studio D process, explores how and why we use photography in research project deliverables today—from the fundamentals of human cognition to the norms that guide photographic practices—to cue up the question: how might processes and behaviours change in the paradigm shift?

// See also: the Photography in the Paradim Shift Masterclass //

Photography consistently provides highest return on investment

In Studio D research photography has consistently delivered the highest return on investment of any data type we collect. This isn’t because we hire dedicated photographers—we mostly use non-professionals who take on photographer duties as part of their other work. Rather, we’ve figured out a streamlined process that can engage all members of the team and which compliments rather than overwhelms their other research activities.

FIGURE 1: The weight and fluidity of data

Photos that generate the highest engagement are true to the research locale and provide a ring-side view on a hot-button issue that the organisation is facing. They can communicate a self-contained story and/or draw the audience into a wider body of research. Whilst mostly viewed in the context of a report, individual photos plus a question, quote, data point or insight have the highest fluidity within an organisation in relationship to their weight—the effort to required to collect, manage and make sense of, and share.

FIGURE 2: Project photography workflow

On a single cross-cultural project with three weeks to collect data, we typically end up with a “working archive” of between 10-15k photos. This might sound like a lot but when split between the team, the number of days on the ground, and home contexts where there is a lot to document, the numbers soon add up. To build and maintain quality we provide around thirty-minutes of upfront training, plus ongoing support, crits/reviews and other related quality control processes.

As a rule of thumb, hiring professional photographers leads to smaller archives containing a similar number of strong photos, but this is traded off against less-contexts visited, and weaker-representativeness of what the team finds relevant—making them less suitable to apply to downstream activities.

From this working archive, we typically generate:

- a project archive of between 50-150 photos that can be widely used by the team internally, and,

- a comms archive of between 3-15 photos that are suitable for use outside the organisation, e.g. for conference presentations or for print media.

Usually, 30-80 photos are used in project reporting, and 3-5 are frequently shared to “represent” the project and are widely used for engagement with the deliverables.

Analysis of photography use

Whilst photos travel further, faster as atomistic units, their primary use is in research deliverables. The following is an example of an executive summary deck showing photographs in purple, text in green and frameworks in blue. In this example, photographs are used for:

- scene setting,

- to provide detailed context,

- to balance information density,

- a teaser to draw the reader into the main report, and,

- and as a reward for reading other text/information heavy content.

FIGURE 3: Example of photo use in an executive summary deck

Photography's other golden ratio

Novice photographers often assume that high-end equipment is paramount for good research photography. Our heuristic is that with today’s mainstream technology, the “right gear” only accounts for 10% of the quality, whereas 50% is about being in the right place at the right time with a camera and that skill accounts for 40%. Field research provides ample suitable contexts, and on-the-job training supports skill development. Thus, a primed team is in a good position to generate a strong archive.

FIGURE 4: The other golden ratio to deliver a strong photo archive

What we're aiming for

Our goal is to build a representative, accessible and versatile project archive of high quality, appropriately sourced research photography. The optimal working archive is representative of what the whole team considers worth paying attention to and enables us to communicate:

- the feel and tonality of a locale,

- deeper contextual understanding and higher emotional engagement compared to other data we’ve collected,

- direct comparison e.g. between participants across one locale or multiple countries,

- provides detailed information, for example around service norms or product use, and,

- reinforces the ethical stance of how the research was conducted.

In many contexts taking photos may lead to social and ethical violations—a camera and the act of documenting a space can be invasive and negatively impact the relationship between the subject/participant and the project team. On some Studio D projects appearing in photos may also present a significant risk to research participants. After many years of trialling different approaches we refined a Studio D process called Full Circle Photography Collection that effectively shepherds team members into legally and morally appropriate behaviours and practices.

FIGURE 5: Full circle photography collection

Why do photographs have potential for such a high return on investment?

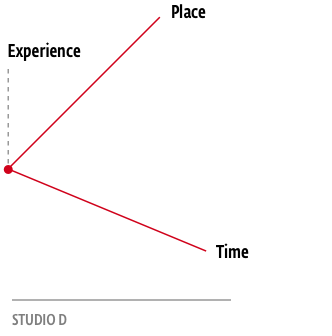

- At a high level photographs allow us to effectively transcend the time and place of experiences—such as events, emotions,, ideas, and things—and allow others to also appreciate those experiences, at a time and place of their choosing.

FIGURE 6: Sharing experiences over time and space

- The images are realistic, as in, similar to the retinal image that is formed if a person were to experience that situation in real life, and they elicit reactions in certain areas of the brain similar to events see in the environment.

- They can be quickly and effortlessly understood, for example taking in a lot of information with a single glance.

- Beyond in-person conversations, they are the primary means by which humans share experiences and are inherently fluid.

Reflecting forward

Can our understanding of photography's evolution provide insights to new behaviours? The following shows a rough timeline with advances in tools and how they have shifted the photographer/photographic-subject relationship. It opens the question of how these norms will changes to the current advances in technologies.

FIGURE 7: The evolution of the photographer/photographic subject relationship

Enter the paradigm shift

In 2023 we saw significant advances in Generative AI images and computational processing—which we believe will be comparable to the paradigm shift from analog to digital photography. How might these changes supercharge or overwhelm your project?

Last month I wrote that in order to elegantly navigate a paradigm shift we need:

- a deep understanding of the fundamentals of what came before in a given domain,

- acknowledging why current practices and processes evolved into their current state, and,

- a set of principles for a given domain to guide decision making for the new reality, plus experimentation to apply and stress test those principles.

As new photographic tools and processes emerge, what should we systematically adopt, prudently adapt or judiciously ignore? The following is one example, from over thirty that we ideated in an afternoon.

An example of practice norms today

Our community has established practices that enable our research audience to establish the veracity of what we share, similar to the benchmarks they expect of other forms of data. To meet this veracity threshold research photography draws on established practices and norms from other forms of research, plus documentarian-, photojournalism-, street-, and studio-photography. Within these norms, a single photo of a person can represent that person, but we are also comfortable when it is used to represent an archetype drawn from many research participants. This might seem trivial—this framing is part of what makes it a norm—but in effect we have callibrated our assumptions of the “veracity of representation” to encompass this abstraction, because of the value it serves the photographer and the audience.

By the same reasoning we can ask: how will today's norms around the veracity of photographs be changed by the paradigm shift?

An example of practice norms adapted for Generative AI imagery

Today a project’s working archive (the 10-15k photos) enables us to generate a high quality project archive (50-150 photos) and comms archive (3-15 photos). To these we might add a Generative IA training archive that can use support numerous downstream activities, such as:

- to obscure personally identifying information such as faces, whilst retaining the aesthetic and sense of “wholeness” of a photo,

- prototypes being used in a range of new (un-photographed) situations,

- provide richness to scenario planning, with “generative characters” being built from participant training data,

- modelling behaviours inside and outside the home (especially when paired with lidar maps of those places), and,

- generate a first pass at marketing and communications collateral for a product launch.

FIGURE 8: Project photography workflow with generative imagery

Of course, just because we can do this it doesn’t mean that we should. There are significant ethical and legal issues to address, for example: informed data consent and model release, appropriate participant rewards that cover new scenarios of use, data-retention practices, guardrails around how a person’s likeness is used, and an updated author/audience social contract that relies on accurate representation of what is shared.

My visceral reaction to this example scenario was critical—as anything that challenges a hard-fought, ethically grounded practice should be. However, in reflecting on how we got to where we are today, the broader societal shifts in how images are created and used, and in thinking through the value-add to organisations, I now consider this ethically, technologically and practically feasible. Perhaps even desirable.

What's next?

I recognise that “research photography” might seem like a niche within the niche of ethnographic research, but my sense if that it won’t only survive the paradigm shift but will come out the other side core to how we collect and communicate research findings, and will have a considerably larger impact on downstream activities. The lessons learned from exploring changes in the niche of research photography can be applied to multiple domains.

What the new community norms should be is very much down to you, and the conversations that follow—with our colleagues, audiences, the participants and the communities in which they live.

To help you navigate these changes I'll be running a Photography in the Paradigm Shift online masterclass that pulls together these disparate threads. Full masterclass description.

//

—Studio D founder, Jan Chipchase

Header photo: Multigenerational household, Lashio, Myanmar.