Photography has consistently delivered the highest return on investment of any data type we work with, despite only twice hiring dedicated photographers in the past decade. In this article I’ll explain the rationale for this claim and unpack the Studio D photography approach and workflow that make it possible.

Previous articles in this series explore the evolution of understanding, introduces the concepts such as the weight and fluidity of data that affect how research deliverables are shared, and organisational data metabolism to frame how organisations think about and act upon different data types. This foundational understanding will cue us up nicely for the final article—to understand the paradigm shift of generative AI and computational processing on image creation, and by extension, the use of photography for sensemaking.

Background

For readers that are new to Studio D—we specialise in cross cultural ethnographic research for corporate clients in the service of product, strategy and communications. We often take on complex, ethically challenging projects across the globe that require us to interact with a wide spectrum of people, from societal decision makers to others at the fringes of society, in addition to the more typical participant demographics. All projects generate qualitative data, and include sensemaking quant and analytics.

Our team in each locale is usually made up of five to six international and local staff, so that the total project team size across cultures can be around fifteen people with diverse backgrounds and skills.

The power of original photography

In Hunters and Gatherers of Pictures Kislinger and Kotraschal (2021) posit that photography has become a human universal citing reasons such as:

- the images created are realistic, as in, similar to the retinal image that is formed if a person were to experience that situation in real life,

- social norms around sharing photographs are driven by indirect reciprocity and reputation management in complex social systems (see also Broekhuijsen et al.),

- they can be quickly and effortlessly understood, for example taking in a lot of information with a single glance (see also Hafri et al.), and,

- photographs allow us to effectively transcend the time and place of experiences—such as events, emotions,, ideas, and things—and allow others to also appreciate those experiences, at a time and place of their choosing (see also Tulving).

FIGURE 1. Photography to transcend the time and space of experiences

The context to this is the now ubiquitous presence of high quality camera equipment—often in the form of smartphones—and the skills to use them, and widely adopted, socially driven services that allow experiences to be shared, e.g. to reinforce social identity, and project status.

In sensemaking organisations the value placed on photographs is grounded in authenticity, something that is now increasingly challenged by Generative AI. In the next article I'll explore how we might address the threats and leverage the opportunities from this seismic shifts.

Research photography norms

There are many genres of photography each with is own entrenched norms and audience expectations. For example, a photograph that appears in the New York Times is held to a different set of assumptions and standards than one that is posted on social media, printed in a fashion magazine, or appears in an online real estate listing. These assumptions include:

- the photographer/photography-subject relationship,

- consent,

- where and how a photo was taken,

- captioning and attribution,

- payment or other reward,

- perspective or stance, and,

- acceptable levels of manipulation

Research photography shares many norms with photojournalism, with some notable caveats. These norms include assumptions around:

- authenticity,

- informed consent, and a clear distinction between organisational-internal and -external use,

- obscurification of personally identifyable information (PII),

- a “do no harm” ethical stance, and,

- an effort to limit biases in how the photos are presented.

Examples of how research photography diverges from top-tier photojournalism norms include: rewarding participants (often as part of an home visit and interview); the acceptance of abstracting a single research participant photo to represent an archetype that includes data from other participants; and staging situations to be documented e.g. “show us how you…”. These might seem trivial—its one of the things that makes them norms—but reflecting on why they are mostly deemed acceptable within our field provide insights to how these norms might change when we explore the impact of Generative AI and computational photography in the the next article.

The changing relationship between photographer and research participants

I first started research photography in the early 2000s as a green usability engineer at Nokia. Early examples of that work that made it into the public domain include Informal Repair Cultures for Mobile Phones and Physical Phone Personalisation, with related (non-commercial examples in the archives of my personal site, and more recent public domain reports on Studio D (which are always a team effort).

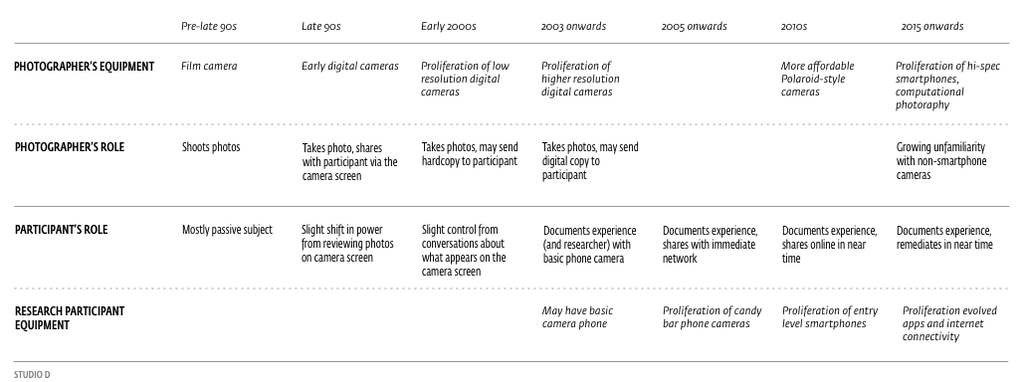

The relationship between research photographer and research participants has evolved over time, often prompted by the mainstreaming of high quality photography equipment, related apps and services, and internet connectivity. When I started researching in countries like India or Brazil the level of participant engagement was limited to either for them to review photos on a low-resolution screen after they were taken, or to empower them to take photos themselves. Today photos taken by participants of the research team are often online before we’ve arrived back at our guest house. This shift in power and control affects what is taken and how it is used.

FIGURE 2. The evolution of research photographer and participant dynamic

Full circle photographic data collection

In many research contexts taking photos may lead to social and ethical violations—a camera and the act of documenting a space can be invasive and negatively impact the relationship between the subject/participant and the project team. Given where Studio D operates and the themes we research, appearing in photos can also present a significant risk to research participants.

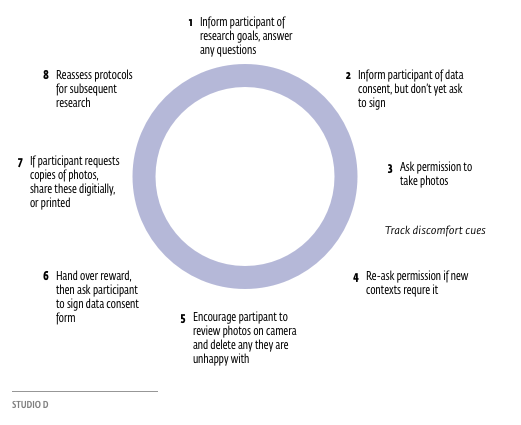

FIGURE 3. Full circle photographic data collection

After many years of trialling different approaches to we developed a Studio D process which we call full circle photography collection that effectively shepherds team members into legally and morally appropriate behaviours and practices. The knowledge that a research participant will be able to review, comment on, and delete any photo they are uncomfortable with fundamentally changes what the photographer captures—and in our experience is a more effective forcing function for ethically appropriate photography than training (especially as we often work with non-professionals).

We also prefer to use dedicated cameras for photography rather than smartphones because it is easier to build and maintain trust with research participants with a dedicated device—through the social theatre of photography, and participant assumptions around how photos will be used. At a high level a dedicated camera implies importing photos and some form of management process, whereas smartphone photography implies sharing, often in the public domain.

Photography aims and workflow

FIGURE 4. Studio D photography workflow

Most of our research projects require us to gather qualitative data—interview transcripts, video, audio, photos and other artefacts in addition to quant data and related reports that are source elsewhere. Almost all of work is client-confidential, but a good example of photography use in a public domain report is Paddy To Plate for Proximity Designs.

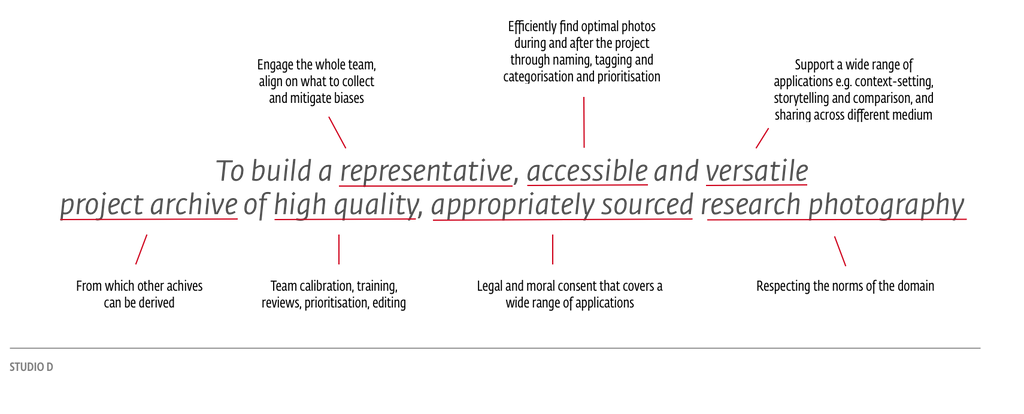

FIGURE 5. The goal of project photography

Our goal on a project is to build a representative, accessible and versatile project archive of high quality, appropriately sourced research photography. The optimal working archive is representative of what the whole team considers worth paying attention (for which a trusted relationship with the local team is paramount) and enables us to:

- communicate the feel and tonality of a locale,

- provide at-a-glance contextual understanding,

- drive emotional engagement,

- provide direct comparison e.g. between participants across a single locale or multiple locales,

- communicate the details, e.g. the steps required to complete a process, and,

- reinforces the ethical stance of how the research was conducted.

Analysis of photography use

Whilst photos travel further, faster as atomistic units, their primary use is in “heavier” research deliverables.

FIGURE 6. Example of photography use in an executive summary deck

The above is an example of an executive summary deck showing photographs in purple, text in green and frameworks in blue. In this example, photographs are used for:

- scene setting,

- to provide detailed context,

- to balance information density,

- a teaser to draw the reader into the main report, and,

- and as a reward for reading other text/information heavy content.

Photos that generate the highest engagement are true to the research locale and provide a ring-side view on a hot-button issue that the organisation is facing. Taken alone (or on a single, easy-copyable slide of a deck) can communicate a self-contained story and/or draw the audience into a wider body of research. Whilst mostly viewed in the context of a report, individual photos plus a question, quote, data point or insight have the highest fluidity within an organisation in relationship to their weight—the effort to required to collect, manage and make sense of, and share.

On a single cross-cultural project with three weeks to collect data, we typically end up with a “working archive” of between 10-15k photos. This might sound like a lot but when split between the team, the number of days on the ground, and home contexts where there is a lot to document, the numbers soon add up. To build and maintain quality we provide around thirty-minutes of upfront training, plus ongoing support, crits/reviews and other related quality control processes.

As a rule of thumb, hiring professional photographers leads to smaller archives containing a similar number of strong photos, but this is traded off against less-contexts visited, and weaker-representativeness of what the team finds relevant—making them less suitable to apply to downstream activities.

From this working archive, we typically generate:

- a project archive of between 50-150 photos that can be widely used by the team internally, and,

- a comms archive of between 3-15 photos that are suitable for use outside the organisation, e.g. for conference presentations or for print media.

Usually, 30-80 photos are used in project reporting, and 3-5 are frequently shared to “represent” the project and are widely used for engagement with the deliverables.

Photography's other golden ratio

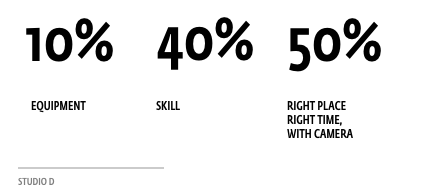

Novice photographers often assume that high-end equipment is paramount for good research photography. Our heuristic is that with today’s mainstream technology, the “right gear” only accounts for 10% of the quality, whereas 50% is about being in the right place at the right time with a camera and that skill accounts for 40%. Field research provides ample suitable contexts, and on-the-job training supports skill development. Thus, a primed team is in a good position to generate a strong archive.

In summary

I started this article with the premise that photography can deliver the highest return on investment of any data type. This claim is based on a process that draws on all team members, regardless of photographic skills, to collect suitable photographic assets that aids their sensemaking, aligns well to other research activities, and has just enough structure to manageable. It taps into the ubiquitous nature of photography in society, the ease with which photographic assets can be shared.

Of course any project can be too over-reliant on photography (as with any type of data). However, as a way of drawing an audience into a large body of work, it is unsurpassed.

Foot notes

References:

- Hunters and Gatherers of Pictures: Why Photography Has Become a Human Universal (2021) Kislinger Leopold, Kotrschal Kurt

- Episodic memory and autonoesis: Uniquely human? Tulving E. (2005). in The Missing Link in Cognition: Origins of Self-Reflective Consciousness, eds Terrace H. S., Metcalfe J. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press; ), 3–56.

- From photowork to photouse: exploring personal digital photo activities. Broekhuijsen, M., van den Hoven, E., and Markopoulos, P. (2017). Behav. Inform. Technol. 36, 754–767. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2017.1288266

- Getting the gist of events: recognition of two-participant actions from brief displays. Hafri, A., Papafragou, A., and Trueswell, J. C. (2013). J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142, 880–905. doi: 10.1037/a0030045

I’m currently working on my next book on human and organisational sensemaking, for which this is part of the research process. Photography seems to be a strong case study to understand the impact Generative AI and other computational processes because it is so ubiquitous.

I’ll be running an online masterclass on Photography in the Paradigm Shift in May 2024. The aim is to equip attendees to elegantly navigate the changes ahead—it is for anyone whose organisation uses visual imagery (not just photographs) for sensemaking and communication. I hope you’ll join.

Header photo: Ibadan, Nigeria.

Personal photography on Instagram here.